Grace Talusan on Her Memoir and Identity

By Kaitlin Milliken

When researching for her memoir, Grace Talusan found pictures of herself as a 1-year-old, mimicking the acts of reading and writing. In 2019, Grace shared her stories with the world in her memoir, The Body Papers.

The book gathers Grace’s essays, touching on deeply personal topics. Her writing explores her cultural identity, experiences as an undocumented immigrant, genetic disease, and her time as Fulbright Scholar in the Philippines. In this episode, Grace shares how writing the book has shaped her life.

You can get a copy of The Body Papers at your local bookstore, or you can listen to the audio book. Listen to the full conversation with Grace below, or subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcast, Google Play, Stitcher, and Spotify.

Transcript

Kaitlin Milliken: Hello, and welcome to the BOSFilipinos podcast. I'm your host, Kaitlin Milliken, And this show is obviously made by BOSFilipinos.

This show is all about telling Filipino and Fim-Am stories in the Greater Boston community. Today’s episode will focus on how the Fil-Am experience has been reflected in literature.

To do that, I sat down with Grace Talusan. Born in the Philippines and raised largely in Massachusetts, Grace is a powerful author, writer, and academic. She is currently the Fannie Hurst Writer in residence at Brandeis University. She has also taught writing courses at Tufts University in Sommerville.

Grace published her first book — titled the Body Paper — in 2019. Her memoir is the winner of the Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing and was a New York Times Editor’s choice. Throughout the memoir, Grace tells her story non-linearly with legal documents, letters, and photos printed alongside her anecdotes. The different chapters cover a wide range of topics. That includes her time as an undocumented child. Her experience as both a Filipina living in the largely-white north east and as an American returning to her home country in adulthood. And family relationships, both healthy and otherwise.

Her descriptions of places in her memoir, from Boston to Bonifacio Global City in Manila, are written with such careful observation and care. Her words are filled with power. I met with Grace at Tufts in November of 2019 to talk about her experience writing The Body Papers. We also discussed the role writing has played in her life.

Before we get started, it’s worth noting: Grace’s memoir is incredibly complex. As much as her story is about joy, celebration, and self-discovery, there are many anecdotes that deal with tough topics. That includes abuse — both sexual and physical — generational trauma, living with mental illness, and genetic disease. Grace and I talked about her experience as a sexual abuse survivor around the 20 minute mark, just in case you want to skip that part of the discussion.

If you’re not able to read The Body Papers due to past experiences, you should still check out Grace’s writing. You can find a selection from her book titled “Crossing the Street in Manila” in Tuft’s Magazine, and “The Thing is, I’m Undocumented” a journalistic piece that ran in Boston Magazine.

Now on with the interview.

So tell us a little bit about the book that you released in April of 2019, for folks who may not know The Body Papers or be aware of the book.

Grace Talusan: The book is a memoir, and it's a bunch of stories and essays about my life. It's nonfiction, so all of it is true. And it's interspersed with documents, and photographs from my life. And they cover a lot of different topics and themes, from my experiences with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, to my experiences as an aunt, as a formerly undocumented immigrant. And as someone who's had childhood trauma, and so it's about a lot of things. And in some ways, it's about the things that we don't talk about. You know, some of the people closest to me were kind of surprised when they read my book, because I hadn't talked with them about the things that I was thinking and feeling and going through. But that's because I could only write them like that's why they exist in the book. It's not really the stuff of conversation. Maybe it should be. At least it wasn't for me.

Kaitlin Milliken: So it's a book that has a lot of opening up being vulnerable. What really inspired you to start the writing process?

Grace Talusan: I've always loved to write. When I was looking at the hundreds of slides that my father took of my childhood, in order to research this book, I came across like two slides, one of me reading, probably at age like one-and-a-half, or pretending to read. And one of me writing, also at like one and a half. So before I could even really read and write, I wanted to do those things. So I think I've always wanted to write, and I've always been a huge reader. And in terms of this book, I didn't know I was writing it. I just was like, writing things that I felt an urge to write. And those pieces started to gather and accrete, and then eventually, I had like enough of these things, to put together a book.

Kaitlin Milliken: So you mentioned that you grew up and are really connected to the Boston area. But you were initially born in the Philippines. Can you talk about your relationship to culture and that move and how you feel as being not only a person who is Filipino, but also someone who's a Bostonian?

Grace Talusan: Boston is a has the...you have the potential that have a very particular cultural identity in lots of ways actually. It could be through sports, like there are people who are like, really into Boston sports. My family, I have family members who are like that. Even though they've moved away, their identity is around being a Patriots fan, or a Sox fan. That's not it for me. But I still do feel really tied to this place. I've been here since I was two except for some times off and on. And I really like that I can feel tied to a place.

It's not like it's the friendliest place in the world. It's not, you know, particularly like people have complained about Boston is really like racist. Yeah, like most things that all might be true. And I have experienced some of them. And yet, because this is the place that I came to after being in the Philippines, I do feel like it's home. And that's really important to me to have a place that I feel like is home. Because one of my first experiences of life is having my home taken away, or like leaving my home, of the Philippines and not having the choice at all. Like I had this whole life going on. We left when I was two, we lived in a family compound. I had a nanny that was with me, 24-seven. Not all the time, of course, she had days off, but like, I have this unknown person who was like my caregiver all the time. I had family around all the time. And we left it, and we came here to Boston. And you know, that's like a really jarring experience.

I thought I wanted to be Irish for a long time. Like, it's kind of a bit like celebrating St. Patrick's Day would be big here when I was growing up. People would wear their green. My classmates who were of Irish heritage, like really got into it. And I wanted to be Irish, like I would wear green. And I would wear stickers that say, “Kiss me, I'm Irish,” because I very much wanted a cultural identity to belong to. And it took me a while to warm up to the Philippines as being that identity, having a Filipino cultural identity or whatever that means.

It's something that is dynamic and that I'm still figuring out after like, a lifetime. The book is framed by a six month trip that I took to the Philippines. I lived in the Philippines for several months on a Fulbright Fellowship. And that experience taught me so much and including like, I am an American. I don't know a thing about the Philippines. I'm Filipino, but I'm not also. I don't have the language skills. I don’t have like the sense of my body, the sense of humor, the kind of ways of relating that I saw people relate to that I think is so beautiful. It's kind of intimacy among strangers that I saw this way of thinking of each other as brother and sister. At least that's what I interpreted. There was this kind of warmth that I saw all the time.

That's not me. I didn't grow up that way, but I admire it.

Kaitlin Milliken: The differences you notice, things you related to, things that seemed distant. Can you talk a little bit more about what you learned and experienced while you were there?

Grace Talusan: You know, family's really important to me here, I see that. And there's ways that like, some people might think my boundaries or our boundaries with family, are unhealthy or something, but I don't think so. I mean, there's a closeness that I think is comforting and that I don't think it's unhealthy. And then I went to the Philippines and I'm like, “Yeah, I get it even more.” They are enduring, an hour and a half, three hour daily commutes in traffic in really crowded, hot conditions crammed onto jeepneys or on buses standing. They're enduring a lot, and it's for their family. Or they have to go abroad or they are what's called temporal migrants where they work the night shift in call centers to serve us in the West. Meanwhile, their family is living in the daytime, and they're working at night, right? So they're these temporal migrants. And like they will do all of that for the love of their family. And that really came through to me this kind of, you know, and I don't just mean blood family, but whoever they decide is their family. I saw that and that was just really really inspiring and beautiful.

This kind of devotion to each other was incredible because I was like a whiny, spoiled American. Like there's traffic it's too hot. The air conditioner’s not working. I was totally like a lightweight, and people were enduring so much with a much better sense of humor and attitude than I was.

Kaitlin Milliken: So you mentioned the book is framed through your journey there. Another important theme is bodies. It's called The Body Papers. Can you talk a little bit about the title and what role the body plays in your memoir?

Grace Talusan: It is a book about what it means to have papers attached to your body, that decide what your life is going to be, and where you can exist. I'm thinking particularly about immigration documents, and how those kinds of papers really impact someone's life experience. And we know now that like, horrible experiences that people are enduring on the southern border, because of lack of papers or not the right papers or something. And just like someone is more human, or treated more or less human, because of that documentation, and how I just find that unconscionable. And so that's so that's some of what I write about is my experiences.

My experiences were really not that bad. I didn't suffer that much as an undocumented immigrant in the ways that I see people are suffering today. But I had a little bit of insight into it by having the same experience of not having proper documentation.

The other kinds of ways that the body is in the book is that I got paperwork that gives me test results that told me that I had a really high susceptibility of breast and ovarian cancer. And so I had to make a choice like, “What am I going to do. I have this for knowledge. Am I going to wait for cancer to develop?” That seems like a really bad idea. Some people think it was a good idea, because they're like, “Well, why would you cut and remove healthy organs?” But the counter to that is, “Well, then why would forego this genetic fore knowledge? That something is about to happen and not prevent that from happening.”

I really, I mean, I thought a lot about it. Talked to a lot of people, studied a lot of like, studies and scientific outcomes, and talked to doctors and all kinds of things. And I just kept coming back to the same — the only answer at this point, and I didn't like the answer, but I also was not about to go get cancer like, and wait for cancer. I have known people who died of cancer, like they sure they treated it, which was quite horrible. You know, the chemo and the radiation are really difficult. And then you might still get cancer like it could come back. It wasn't easy, but eventually I felt really lucky that I had this knowledge and that I could prevent it like my sister, my other relatives and cousins they did not, and they live with various levels of fear about cancer, including one cousin —who she has metastasis to the brain and from her breast cancer, and she's just been living with it for years. And I just think, “Oh my gosh, it's like this tipping point. Like, will you have to keep taking the medication and hoping that it's going to work? But what happens when the day it doesn't? And so I needed to do something.” And that's what I did is I traded up or traded away my healthy organs for not getting cancer.

Kaitlin Milliken: Having the mastectomy is definitely an exercise in like autonomy and being able to make your choices, which is great.

Grace Talusan: Yeah. You know, my nieces are getting older. And you know, I think about them. But I do think the word autonomy is the right one, it's like they have to make the choice. We’ll be there for them and support them. If they find out that they also carry this genetic mutation, but it is up to them in their life, and they have to make their own choices.

Kaitlin Milliken: You mentioned immigration, which I know is something that's on the forefront of everyone's mind all the time in this day and age that we're living in America. Did you decide to share those experiences because of the political climate when you were writing the book? Or was that something that you had decided to include much earlier, when you first began the writing process?

Grace Talusan: I very much only wrote about it because of the political climate. I was always told to never talk about it. And in some ways, I could just pass and move on, right? Like, I had my US citizenship. I have my blue passport. I don't actually have to deal with it at all. But I started to meet people, including students who were undocumented. And I thought I realized like, “No, I'm safe, and they're not. I need to do something.” If my story can do anything to help understanding around this issue, I need to do it because I'm safe. And so I was reporting for Boston Magazine on a high school senior. And that's when I started to write about it. And I just saw her and her bravery and about telling her story and also how stuck she was. She had some really low moments.

And that's when I thought, like, “I can't keep my story actually, is important in this situation, because I was also at one time, a high school student who was undocumented.” And that's when I started to tell that story. And then I interviewed my parents. And then later on, I even did a FOIA request, and I got 100 pages back of documents from the government. And, you know, that became important because children were being separated from their parents at the southern border. And I was so upset by that. And then I was looking at the paperwork that I got back from Immigration and Naturalization Services, and they said all over it, “She is a nine-year-old child.” They wrote it in big writing all over my documentation, as if to remind the arresting officers and the other immigration officers like, have compassion here. Like she is a nine-year-old child. And so I really appreciated that, that they had that kind of discretion. And they listened to the story of my family, and that we were a mixed status family. We had it. My parents owned a home. My father had a business in which he employed people. We had US citizens, children, in our family, and they didn't disrupt our family. They let us stay together until all the documentation was cleared up. And I really did appreciate that.

Kaitlin Milliken: So you mentioned you interviewed your parents, you did a FOIA request. That's a lot of researching. And I know most books take research, but it's not always about you as an author. So how did it feel to really research yourself and take that time to be very introspective about your life?

Grace Talusan: Well, I have, because I've done some reporting, as a freelancer, I wanted to use those same skills in writing this memoir. It actually didn't feel right for me to just base it all on memory. I think it's possible, that it's fine. Like it's a memoir, it's based on your memory. But in terms of the story I wanted to tell, I felt more ethically comfortable if I at least tried to verify the things that I was writing about. And I discovered that I was actually wrong. Like the story I've been told is that I came to this country when I was three-years-old in the winter. And that's not true. My paperwork showed that I came here at age two in July. And so like my parents had just kind of forgotten. I don't think they meant to it's just that that's my memory started in my memory corroborated their memory because I remember being really cold. I remember sitting on Santa's lap. It was like snowing in Chicago, like I remember all these things. But that's when my memory begins. That's not where my story in the US actually begins.

So I was glad that I got this outside documentation, because it taught me things about memory and storytelling and like, “Why was that story so important to me about being three? And it's snowing, when actually it wasn’t. It was the summer.” And I was like, “What does all that mean?” But I also think facts are incredibly important. If you have the opportunity to verify and have like other kinds of documentation, why not? Like, why wouldn't you do that? Unless you're trying to do some other kind of project about memory, that's fine, but it just seems like there's great information there to use, including photographs. Like there's so much information in photographs.

If you're writing a memoir, I would recommend you utilize all of it, including maps, like go on Google Maps and like, take a walk inside like a former neighborhood or something like that. It's all like really great material.

Kaitlin Milliken: I know something else that you discuss in your book is that you are a sexual abuse survivor. Can you share a little bit about the process of writing that portion of your story?

Grace Talusan: Because I was looking through all my archives and papers that my father had saved, like he saved my school papers. One of the things I came across was that I actually wrote and turned in an essay about it in high school, like, just two years after I told my parents. I had written about what had happened to me. It's pretty similar to what I have in the book, because it was… What happened to me was pretty repetitive. And so there wasn't...it wasn't going to be like so different from what I wrote about. So I've been writing about it for a long time, but not publishing about it.

So in graduate school, I wrote a pretty close novel that was really close to my experience autobiographically. And I wrote that I didn't publish that material, but I have been interested in the material in a long time. It's not like I want to write about it. I'd have to work up to write about it, because it's not something I want to do. But it has felt important to do it. And so when I wrote the version for this memoir, I showed my writing group, and some people in the group said, like, “Well, what happened? Because like, you never actually write about what happened directly.” And then I realized, like, “Okay, I guess I have to do that.” And so I did.

So I thought very, a lot and deeply and closely about like, what am I going to say about my experience, and why would I say it, and what will I leave out and why would I leave that out? And so ultimately, I thought that he would do more damage if I didn't...if I was not transparent and just matter of factly said, like, “This is what happened.” Because I just didn't... I wanted to be transparent and say like, this is what happened, and it was very repetitive. And so that is the thing that happened very repetitively for seven years. And so, it taught me a lot because like, I don't want to talk about it. I don't want to think about it. But it forced me to, and it forced me to contend with the kind of damage that I mean. I wish I just want to pretend it didn't happen. But when I wrote about it, I'm like, “Oh my gosh, okay, almost every night for seven years, for basically my entire childhood. Like, oh my gosh, how did I even deal? How did I get through the day?” I mean, all those things.

I was able to see it as an adult and have much more compassion for myself. Kind of give myself a break. Like, that's kind of why I struggle with some of the things I struggle with to this day. You know, it's a pretty big trauma. And I've done a lot of work to deal with it. But, um, you know, at one of my, my first readings in Seattle, someone in the audience to ask me if I was healed yet, from what happened. And I was, you know, I mean...I took the person seriously, but I was also kind of angry about the question. And I was just like, “No. Healed. I mean, what does that even mean?”

Am I going to be healed from it in my life? I hope so. I think I just learned to grow around it and like, move, create a life around it, but heal to me means it like connotates something like that or know something different like almost like it never happened or something. But I mean, my symptoms are very... I don't suffer the extent of the symptoms I did when I was, you know, 10 years ago or 20 years ago. I don't suffer those symptoms, but there are reverberations still in my life for sure. But writing about it was a another kind of way to process and another way to approach some kind of — not healing — but like a way to deal with it.

Like if part of the issue around it was keeping it secret, the fact that I did the exact opposite of that, and put my story in a book that exists all over the world and including sitting in libraries, and in bookshelves, and in Amazon warehouses and whatever, like, that means something that's meaningful to me that I didn't just keep it and like die with this story, but I put it out in the world and that's meaningful to me.

Kaitlin Milliken: Coming through the end of that writing process, do you feel like your relationship or understanding of yourself has shifted at all? Has it changed your relationship with yourself?

Grace Talusan: I think writing both writing and reading are really profound activities that have the potential to change you. Yes. And in my particular case, yes. As soon as I got the book deal, something in me changed. And then the process of working with my editor and publisher to develop the book, revise it, go through all the steps of copy editing, and making it into what I think is a beautiful object. That changed me. And then even recording my audio book changed me. Like the person who recorded the book with me, he was my engineer, you know. He sat with me for a week for hours every day. He was so kind and so gentle. And it was my first time recording an audio book. And like that was a really wonderful healing experience to like, tell my story to this audio engineer.

It was, I don't know, there's just all these experiences that I've been able to have from the act of publishing that I would not have had if I had just stayed despairing and depressed, and not just like thought the things I was thinking before I got the book deal, which is like, “Nobody cares about my story. No one wants to publish it. And you're like, I'm just a loser.” You know, those things aren't true. I don't think those are true if people haven't published a book and have wanted to, but that's how I was feeling. I was feeling pretty bad about myself. But you know, as bad as I ever feel, there's always a part of me that wants to fight. So even though I was feeling bad about my writing and thought, like, “I'll never publish a book,” I still did enter the contest, there was still a part of me that wanted to keep going and fighting. And I entered the contest, like, I never thought I would win. And yet I did.

And so those are, those are things that changed me. And then like reading the book, like I know I wrote the book. So obviously, I've read it. By the time we were done with the very extensive revision process, I almost didn't even know what I had anymore, because I was looking very closely at like sentences as at the space between words at commas at this section, that section. It's like I couldn't see the whole thing. And so I got it back. And I got the hardcover in Seattle, that was the first time I saw it. And then at some point, I read the book and I was like, “Oh my gosh, this is a book about my father. What have I done?” Because I did not expect that it was a book about my father. I thought it was about me. And yet it was so much about how I understand myself, and which is understanding myself through my father.

Kaitlin Milliken: That was really great. I definitely understand the process of like, when you look at something for so long, that it just starts to become its own very small fixation, instead of looking something up as a whole picture.

Grace Talusan: Yes, yeah. And by the time this comes out, probably my paperback will have come out or be about to come out. And what I'm in the process of doing now is trying to look at the book holistically, and take out some errors or repetitions or things like that. And so now that the book is a thing, I can go back and like go back in and try to make some corrections and change some things, some tiny, tiny things that I saw as errors now that I can see the whole book.

Kaitlin Milliken: So this is my final question. What do you hope readers will take away after they complete your book?

Grace Talusan: That's a really great question. And it is a privilege to even think about that question. So I wonder if there is a story that you don't tell, even to yourself. And if so, why is that? Like, what is that part of yourself that you don't even want to touch? And what would it mean to attempt it? And I don't mean like, you should do this. You should do this in a safe way. Like, if the best, safest way to do this is with a trusted therapist, like definitely do it that way. But I just wonder, you know, why do we want to hide things from our own self?

And then if you go beyond that, and think like, what are the things that we need to share with each other? And we need to tell each other. Part of the reason I was driven to publish this book is because I thought about the next generation like my students, my nieces and nephews, my nibbling, like, I want them to have the truth. I want them to be equipped with the full truth of things, even though it's painful sometimes when it's appropriate for them to know the truth. It's better that they know what then they not. Like, in a way people lied to me and told me, you know, and I wanted to believe a story about my grandfather, and it actually wasn't true. And it kind of ruined or like, in lots of ways, ruined parts of my life. And like, almost destroyed it because I didn't have the truth. And so I think the truth is really important.

And at the very beginning, we need to start with ourselves. And then we have to start to think about like, what would it mean to tell the truth in this relationship or that relationship? And I think it's worth it to try and to see how your life might change for better or probably will change for the better. And like that secret that you've been holding on to, maybe you shouldn't hold on to it.

Kaitlin Milliken: Definitely. That's very powerful. Thank you. Thank you so much Grace again for taking the time out.

Grace Talusan: Oh, this has been such an honor. Thank you for interviewing me and this opportunity to talk.

Kaitlin Milliken: This has been the BOSFilipinos Podcast. I’m your host, Kaitlin Milliken. Music for this episode was made by Matt Garamella.

Special thanks to Grace Talusan for sharing her story. If you haven’t already, read The Body Papers and experience her writing first hand.

Before you go, Friday June 12 is Filipino Independence Day. Even if gatherings are still restricted, we hope that you can share Filipino culture and heritage with the people you care about. You can also keep up with opportunities to celebrate, and other stories from Boston’s Fil-Am community at bosFilipinos.com.

If you haven't already, you can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcast, Stitcher, Spotify, and Google Play. You can also follow us on Instagram @bosfilipinos to stay connected. Thanks for listening and see you soon.

Filipinos In Boston: An Interview With Reporter Elysia Rodriguez

By Trish Fontanilla

This month’s Filipinos in Boston highlight is Elysia Rodriguez! We first connected on Instagram a few months ago, and I was so excited to hear that we had some representation on local TV. Although glancing at the Fil-lennials of New England feed, it looks like we have a handful of Filipina reporters in our midst!

Hope you enjoy our profile of Elysia, and if you or someone you know wants to be highlighted on our blog or social media this year, you can fill out our nomination form.

Photo provided by Elysia Rodriguez.

Where are you and your family from?

Elysia: I was born in Florida but moved to the Philippines just before high school and lived in Metro Manila. I went to Dominican High School in San Juan before coming back to the US for college.

My father’s side of the family is originally from Sorsogon but my immediate family now lives in Antipolo.

Where do you work and what do you do?

Elysia: I am a reporter for Boston 25 News.

How did you get into broadcast journalism?

Elysia: I honestly have wanted to be a reporter for as long as I can remember. My father is a musician and taught me to be confident and how to perform. However, instead of entertainment, I chose journalism. I love getting to the bottom of an issue, I love telling stories that impact people, and I love getting to know members of the community in ways that my job gives me access to do.

On Boston…

How long have you been in Boston?

Elysia: About 6 years.

What are your favorite Boston spots?

Elysia: I love the MFA and the New England Aquarium (I used to volunteer there as a penguin aquarist).

My two dogs and I love Copley Square - they love that they’re allowed to walk into the Fairmont Copley and say hi, and then also say hello to each and every person who lets them on Boylston and Newbury.

Photo provided by Elysia Rodriguez.

On Filipino Food...

What's your all time favorite Filipino dish?

Elysia: I like the simple classics (basically the ones I know how to make) adobo, chicken not pork. And pancit bihon, because I can’t eat gluten. I can also inhale a platter of suman.

What's your favorite Filipino recipe / dish to make?

Elysia: Pancit - it’s really beautiful at the end, or halo halo because there are just so many colors.

Photo provided by Elysia Rodriguez.

On staying in touch…

How can people stay in touch?

Elysia: They can find me on instagram elysiarodrigueztv or my website elysiarodriguez.com - those are the best.

We’re always looking for BOSFilipinos blog writers, so if you’d like to contribute, send us a note at info@bosfilipinos.com.

Podcast: Trish Fontanilla on Founding BOSFilipinos

By Kaitlin Milliken

If you’ve ever been to a BOSFilipinos event, you definitely know Trish Fontanilla. She’s the one running the show. She’s also the person who does most of the BOSFilipinos spotlights and the group’s newsletter.

In this episode of our podcast, we put Trish on the other side of the interview and ask her about founding BOSFilipinos. Trish also shares her experience growing up as a Filipino American in New Jersey — including why she grew up with two birthday parties.

Listen to the full episode below, or subscribe to the show on Apple Podcast, Google Play, Stitcher, and Spotify.

BOSFilipinos Podcast Episode One: Introducing Your Host

by Kaitlin Milliken

Most people who grow up in the US as a -American have a complicated relationship with culture. Maybe you’re teased for it. Or you have a dual identity between your classmates and your cousins. Or you compartmentalize how you act at home from the rest of the world.

As a kid, I always felt too American when compared to my Asian-American classmates and friends. I only spoke English and preferred pasta over palabok. I saw culture as a checklist. If you filled in enough boxes, then you could call yourself Filipino.

When I moved to Massachusetts for college, my experience flipped. At Boston University, I was one of a few people of color in groups. I began to see how my background shaped my worldview. Being Filipino-Japanese-American became a larger part of how I defined myself.

In the first episode of this show, I take a deeper dive into my relationship with Filipino culture. I also sit down with my grandma to get a better sense of the family history and her journey to America. I hope you enjoy listening as much as I enjoyed sharing this story.

Transcript

[MUSIC]

Kaitlin Milliken: Hello, and welcome to the first ever episode of the BOSFilipinos podcast. I'm your host, Kaitlin Milliken. This is a brand new podcast created by, you guessed it, BOSFilipinos. For those of you who don't know, BOSFilipinos is a volunteer run organization that aims to elevate Filipino culture in Boston. This podcast is one way that we tell those stories. The group also has a blog and an Instagram which you should also check out.

In each episode we highlight a different aspect of the Filipino American experience, from language, to food, to dance, and so much more. Our show is going to be Boston-centric, sharing Filipino stories from the Bay Sate. But we'll also talk about people promoting FilAm culture from other parts of the country.

But before we dive deep into all of those topics, I'm going to spend our first episode introducing myself and talking about my relationship with culture. To do that, I want to start at the very beginning by talking to my grandma, Odette Semana Rojas.

Odette Rojas: Okay, when do you want me to start?

Kaitlin Milliken: So tell me where you grew up in the Philippines.

Odette Rojas: I was born in May of 1946 in San Juan, Batangas, in the Philippines, and we migrated to Manila, when I was two years old, and that's where I grew up. It’s also called San Juan Rizal. I went to public school there. And then when I went to high school, my mom, my dad enrolled me in a private school, which is called Forresten University, where I also finished my nursing career. And I got married in 1967, and we migrated to the United States with a child, and it's your mom. Her name is Maria Ayna Rojas.

Kaitlin Milliken: So we’re gonna go back, like a while. I feel like we just went through, like 40 years in like five minutes.

Kaitlin Milliken: In this recording, I'm sitting with my grandma in her house in San Jose, California. My mom and boyfriend are sitting on the couch off to the side attempting to be a quiet audience.

My grandma is the coolest person I know. I always picture her as this radiant woman with an unforgettable smile. She has an objectively better taste in fashion than I do, and never ever wears sneakers. Even as a nurse clogs are her walking shoes.

On top of being an absolute icon. She is also the matriarch of our family. She knows all of the gossip and holds all of our stories close. The CliffNotes version about her journey to the US and have asked her a few questions about her immigrant story for school projects. But this is one of the first times we really dove deep.

Kaitlin Milliken: What was it like growing up in the Batangas? What was that like? I've never been.

Odette Rojas: Okay, okay. Batangas is like a province. That's where I really enjoyed myself when I was young. We used to go to the beach, and we used to play with jellyfish and sometimes it gets caught in your skin. It gets itchy but all you do is rub yourself with the sand and it goes away.

I will walk with my friends and wherever we will take us. When it's raining and there's water flowing water nearby, what we do is we used to use wooden shoes and you can slip it on and take it off. So what we used to do is we race those shoes. We put one of our shoes in the water, and we race the shoe and see who first will go the other end.

The other one too is the, you know, the spiders. It's the one that has the big butt. It’s not the regular spider that has more legs. I don't know what you call it, but anyway we put them in a batch max… What do you call that?

Kaitlin Milliken: Match box.

Odette Rojas: The match box. We put them in there, and then we get a stick. Then one end, someone puts their spider then, and then the other one was deep spider at the other end we did have them fight and the one that false loses the game. [LAUGHS]

Kaitlin Milliken: My grandma grew up with her six siblings in the Batangas, fighting spiders and racing shoes in the rain. When it was time for her to go to university, she decided to study nursing, one of the big professions in the Filipino community. She went to school in Manila writing the jeepney to and from university for the first two years. After that, she moved to the dorm and even with the strict rules of nursing school, my grandma was her usual fun loving self.

Odette Rojas: And I always get involved with activities because even when I was a student and I was the president of our nursing school organization before I graduated. And then besides that, I was one of the representatives of our department to the university that meets with others. That's where I met your grandpa. Yeah, so that's how I get involved. And then when there was, before martial law, I was really married at that time. When I was a student, and I was one of the activists. We used to run around and we had placards about you know, this and that, this and that. And then we go to the classroom and tell them not to go to school and we go out there in the street. And you know...

Kaitlin Milliken: My grandma always knew she wanted to come to America. In one of her journals, she had written that her dream was to move to the US, drive a fancy car, and send all of her kids to school. Around the same time, a number of my grandpa's relatives started immigrating to the country looking for opportunity. He was an engineer, so he was able to get a professional visa. And thus the small family's immigration journey began

Odette Rojas: Using your grandpa's certificate graduating from engineering department, because I didn't graduate at that time, I have to wait another year. I applied for a second type of visa to the United States which is professional, and if you are accepted, they'll issue you an immigrant visa. So we were able to get an American visa, and your mom was born at that time. Your mom was only 14-months when we left.

We stayed with Auntie Dorith, which is your great-grandma's sister. That's where we rented a room. And on the way coming to the United States, all I had was $10 in my purse, and our transportation was fly-now-pay-later. There was such thing before. And it was, I believe it was like $475 each at that time. That was expensive at the time. That was in the 70s. So we stayed here and rented the room with Auntie Dorith.

Kaitlin Milliken: My grandparents lived with relatives when getting their footing in the US. My grandma had to take an exam to continue her nursing career in America. After two tries, she was able to pass, and the rest is sort of the American dream. My grandma eventually got a job.

Odette Rojas: So I got hired at the hospital and I had to work evening shift because of babysitting. So your grandpa and I used to switch. I work 3am to 11am. He comes home at 5 o'clock and takes care of you to care of — not you — but your mom. And so that's how we did it. I worked 3 to 11 and he worked, what do you call it, days.

Kaitlin Milliken: They bought a house in San Jose, California.

Odette Rojas: Then we bought the home, and we could not afford anything so we ended up, as I said, buying stuff from the garage sale. So our plates were like 10 cents apiece. And then the table I think we bought it for five bucks. The two chairs were like $1 each. And they are so cheap when your grandpa was sitting on one, he fell on the floor. [LAUGHS]

Kaitlin Milliken: She got her first American credit card from Macy's to buy better stuff for the house.

Odette Rojas: Mind you the only department store, or any place, that issued us a credit card, because we could not get any credit because we didn't have any credit reference, right? So Macy’s was the first one. That's why I've been with Macy’s for years, even before your uncles were born. So they gave me a credit card good for $500. So we bought our mattress there and the box spring so at least we have a bed. And you're your mom slept with us anyways, so it didn't make any difference whether she has a bed or not.

Kaitlin Milliken: She and my grandpa helped out some friends who also immigrated from the Philippines.

Odette Rojas: Your dad, your grandpa's best friend and another friend needed a place to stay. They came from the Philippines too, and they didn't know anyone. So what I did is I rented the two rooms to the two guys with the food too, so that way, we have enough money to buy the other stuff.

Kaitlin Milliken: They also helped my grandma's siblings and parents when they came to the US.

Odette Rojas: Mama Josie, dad’s mother, had three sisters that were here. It was all on his side, none on my side. So every Christmas then, I always cried because I didn't have anyone. Then my sister came with the husband, and that got a little bit better. And then later on I petitioned for my dad and my mom. And so everybody got here, but it took a while before we got them all here.

Kaitlin Milliken: My grandma had two more kids. She got involved with the FilAm association at the local church; divorced my grandpa; fell in love with my Lolo Sol, who has been like a grandparent to me ever since.

She watched her children grow. My mom got married and at some point in the mix, my brother and I happened. And we grew up with two loving parents, my grandma close by, and the whole Filipino side of the family within city limits.

My grandma and her siblings were the side of the family we spent the holidays with. My idea of Christmas is incomplete without the full spread of my uncle Amado’s cooking. My maternal cousins and I spent summers together. My Tita Baby spent a long time attempting to teach me words in Tagalog, which I never internalized. I grew up surrounded by all of this culture and a large part of that came from my family.

On top of the culture that came from my family, I grew up surrounded by other Filipinos in my community. Most of the students at my middle and elementary school were Filipino, and my high school was also very diverse. Lots of students were bilingual and very in touch with their cultural roots. So I never felt like I was different. Sometimes I actually felt like I wasn't Filipino enough. I wasn't full Filipino. My dad is Japanese and white. I didn't speak the language or own a filipinana. We stopped doing mano-po, where you touch an elders hand to your forehead as a blessing, after my great grandfather passed away. To me, I was just like any other American and way less Asian than other people in the Bay Area.

My relationship with my cultural identity changed when I moved back east. My grandma and mom dropped me off at Boston University in 2014 for my freshman year of college. I was the first person to go to school on the east coast in my family. I studied journalism, did radio, made a bunch of great friends, and met a lot of people from different backgrounds. And of course, going to BU, a good number of my friends were white.

And that's when I realized that I was raised differently. The traditions in my family, the food, the close knit nature of my relatives — that was all a part of who I was, and I missed it. So I went to the internet, more specifically Instagram, to find ways to meet other people from the same background. BOSFilipinos was one of the first groups I found, and they had a meetup that was relatively soon. The rest is history.

At the end of the conversation with my grandma, I asked her what she wanted me to know about being a Filipina.

Odette Rojas: I am a Filipino by blood, and then of course, accepting the way who I am, wherever I go. And then my feeling is we're the same, excuse me, but if we scrape off our skin, my skin will be brown. When we scrape off our skin, my blood and your blood is the same. Maybe we come from a different place, I come from a different place, but that doesn't mean that you're higher than I am. That's why I have an attitude, “If you can do it, I can do it too.”

Kaitlin Milliken: What role do you want Filipino identity to play for like me?

Odette Rojas: I guess. Consider yourself as a Filipino, and just like people here they accept to be American. Just respect each other's values and beliefs. And you take the way you are as a Filipino. You always always have the attitude of respect. Dignity.

Kaitlin Milliken: If you can do it, I can do it. And if I'm going to do it, I'm going to be the best at it. I think about that all the time. I'm still figuring out what it means to be a Filipino-American. But as I search, I think that mantra will be with me all along that journey.

[MUSIC]

Kaitlin Milliken: This has been the BOSFilipinos podcast. This episode was written and produced by me, Kaitlin Milliken. The amazing Trish Fontanilla helped me get this podcast off the ground. Thank you so much, Trish, for everything you do. Special thanks to my grandma and my family for helping me tell my story. If you haven't already, you can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcast, Stitcher, Spotify, and Google Play. For more stories from Boston's film community, visit bosfilipinos.com or follow us on Instagram @bosfilipinos. Thanks for listening and see you soon.

The BOSFilipinos Podcast

By Katie Milliken

As people, we always crave community and connection. In the era of self-quarantine and election cycles, lifting each other up has become especially important. We can listen to other's stories and cheer each other on, even though we don’t share a physical space.

That’s one of the reasons why we’re very excited to announce our new show, The BOSFilipinos Podcast. In each episode, we’ll explore a different aspect of the Filipino American experience, with a focus on members of the Boston community. Our first full episode will come out on April 3rd, and we’ll be posting new content on the first Friday of every month. You can listen to the trailer below.

I also wanted to share a little bit about myself. I’m a Filipino-Japanese American journalist from San Jose, California. Growing up, I was surrounded by the Filipino side of my family and the Bay Area’s large Asian community. When I moved to Boston for university, I missed the cultural elements that reminded me of my home.

So, I began to search out Boston-based FilAm groups and found BOSFilipinos. The more I participated in the group’s activities, the more I wanted to volunteer. Shortly after, I had a conversation with Trish and the podcast was born!

I’ll explore my background and relationship with culture in our first episode. You can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcast, Google Play Music, Spotify, and Stitcher for more updates. Do you have a topic we should discuss, want to be featured, or know anyone we should interview? Let us know by filling out the form below the Trailer Transcript.

Thanks for listening!

Trailer Transcript

Hello and welcome to the trailer for The BOSFilipinos Podcast. This is a brand new podcast created by, you guessed it, BOSFilipinos. We’re a volunteer-run organization that aims to highlight Filipino culture in Boston. I’m your host Kaitlin Milliken. In each episode of this show, we’ll highlight a different aspect of the Filipino American experience—from language, to food, to dance, and so much more. Our show is going to be Boston-centric, but we’ll also talk about aspects of FilAm culture from other parts of the country as well.

Our first episode will be up soon, but until then, subscribe to our show wherever you listen to podcasts. We’ll be streaming on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Google Play Music and Stitcher. You can also listen to the show, read awesome profiles, and catch up with our blog posts at bosfilipinos.com. If you want to be highlighted or know someone who we should feature, DM us on Instagram, @bosfilipinos. Thanks for listening, and see you soon.

Podcast Submission

What's Next for BOSFilipinos

Photo taken / edited by Trish Fontanilla.

Hi BF-fers,

I’ve tried to write this post over the past week but since things kept changing day to day, and honestly, I found myself overwhelmed… as a Bostonian, an Asian American, a freelancer, someone who has one living parent in their 70s, someone that volunteers with vulnerable populations, and as the person that runs BOSFilipinos. I think all of us are feeling some pressure or distress on all different sides of our identity.

“This is just what I needed,” is something that I often hear at BF events. Knowing that our community has created spaces where people feel safe, seen, and included, I was hoping that we’d be able to keep doing our in-person events, but modified. However, as you all know, any kind of in-person event right now is unsafe. So while I feel like a lot of us could use some home-cooked Filipino food and company, I’m postponing all of our events until we know more. Here are a few more bulleted notes about our future plans:

Events (Meetups / Classes / Pot Lucks / Volunteer-led Excursions) - As mentioned, all of our events are canceled until May. Mid-April we’ll reassess and see if that needs to be extended, and we’ll announce that here on the blog as well as on our social feeds (Facebook / Twitter / Instagram) and in our newsletter. We will, however, continue to list community events on our Events page. While we do not encourage public gatherings until it’s communicated that it’s safe to do so, we do want to amplify the efforts of our community so that you can follow those individual organizations as they send out updates / reschedule.

Conversation Circles - People have expressed interest in learning Filipino languages, and we were beginning to do some intake, but these meetups will also will be postponed for now. I’ll think about how we can achieve this online (and not be repetitive with current resources out there), but for now, if you’d like to know more about when this launches, you can fill out this form: https://forms.gle/9dEX9Z5a51iMaaG88 We’re especially in need of people that are fluent!

Profiles - Now more than ever it’s important that we tell stories about our incredible community. So if you’d like to nominate someone to be featured (I’m looking at you too!), and they haven’t already been nominated (we’ll cross check - if they have been highlighted already, we’ll send them a nice note that someone was thinking of them), please fill out this form: https://forms.gle/9dEX9Z5a51iMaaG88 If you’ve already been highlighted but have an update, feel free to use that form as well, we’d love to hear what you’re up to these days.

Volunteer - As many of you know, the core BF team is three deep (Hyacinth, Katie, and myself), so if you find yourself with some extra time and want to give back to this community, we’d love to work with you! We’re looking for people of all backgrounds and skill sets, so tell us more about yourself by filling out our contact form: https://www.bosfilipinos.com/contact

And last but certainly not least… please remember to take care of yourselves during this time (and always!). I know a lot of you out there are caregivers, whether that be through profession, community leadership, within your friend group, or within an intergenerational family, to name a few. It’s absolutely a time to look out for and uplift others, but you can’t do that if you’re not taking care of your physical and mental health, so please take time for yourself however you can.

If there’s any other way we can help you or someone you know in the community, please don’t hesitate to email us: info@bosfilipinos.com.

Love and tabos,

Trish and the BOSFilipinos Team

Filipinos In Boston: An Interview With Artist-in-Residence Hortense Gerardo

By Trish Fontanilla

February’s Filipinos in Boston profile is Hortense Gerardo! Hortense and I actually met at BF’s Filipino food pop-up at Parsnip last month, and after hearing about her show next week, I thought that it’d be the perfect time to highlight her.

Thank you, Hortense, for letting us profile you this month, and I hope you all enjoy our latest FiB post!

Birthday smile! // Photo submitted by Hortense Gerardo

Where are you from?

I was born in Nashville, Tennessee, but my father is from Ilocos Norte and my mother is from Ilocos Sur. Most of my relatives are in Quezon City.

Where do you work and what do you do?

I am the Artist-in-Residence in the Arts and Culture Department at the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC), and my job involves devising creative strategies to promote community cohesion and resilience through art.

What inspired you to pursue that career path?

My work as an Associate Professor in Anthropology and Performing Arts at Lasell College has been an ongoing training ground that honed the multidisciplinary skill set that I bring to MAPC as an ethnographer, playwright, filmmaker, choreographer, and educator. However, the current projects on which I am working, which address issues such as mental health care, climate change, and the opioid crisis, are informing the ways I write and my approach to teaching and collaborating with others. Underpinning all of this is a love of travel and storytelling, and the most compelling way for me to pursue these passions was to become an anthropologist and a playwright.

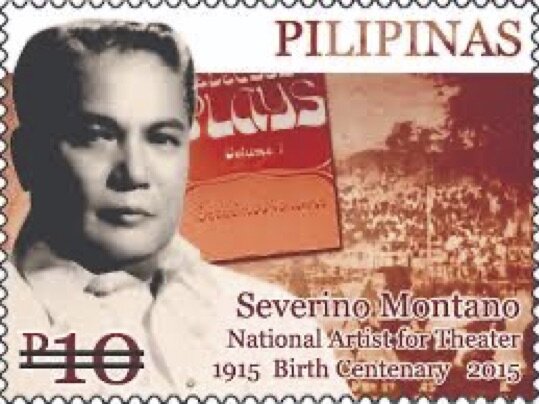

Until recently, I never understood where my love of playwriting came from. I was told I had a relative who was in theatre, but my searches came up empty, in part because I had been searching under the last names of more distantly-related relatives. More recently I discovered the playwright, Severino Montano, was my grandmother’s half-brother, and there was a commemorative postage stamp issued in his name (picture below!).

Severino Montano (my paternal grandmother's half brother) // Submitted by Hortense Gerardo

On Boston...

How long have you been in Boston?

I was at Boston University the year Mike Eruzione scored his goal against the former Soviet Union and won the gold medal for the US Olympic Hockey Team. You can do the math.

What are your favorite Boston spots (could be restaurants / parks / anything!):

I think Boston has some amazing art museums. I never tire of going to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, the Institute of Contemporary Art, and the Harvard Art Museums, all of which not only house amazing permanent collections and exhibitions, but are increasingly the go-to places to attend performing arts events.

What's your community superpower?

I don’t know that I’d call it a superpower, but I’ve been told I listen well and can translate what I hear into the works that I write for the stage or screen. I’ve been fortunate to meet some very generous people with inspiring stories to tell. Most recently, I worked with people from the town of Medfield who shared their stories of the former Medfield State Hospital, which I wrote into a full-length play called, The Medfield Anthologies.

I also worked on a project in which a farmer and a fisherman told me about the impacts of climate change on their respective occupations, and the innovative solutions they’ve found to the challenges they faced. Here are the links to short, documentary “video-lets” I co-directed with filmmaker Monica Cohen: https://youtu.be/oJ2f8XZLGug https://youtu.be/nidApZGs88E

On Filipino Food...

What's your all-time favorite Filipino dish?

Camaron Rebosado is the dish I always ask my mom to make when I visit my parents. I associate it with the big dinner parties they’d host at our house for their friends and relatives. As a kid, I knew there was a special occasion to celebrate when she’d make Camaron Rebosado.

What's your favorite Filipino recipe / dish to make?

My mom’s recipe for Leche Flan is easily my favorite dish to make. It’s that great combination of being delicious and plates really well, yet ridiculously easy to prepare.

On Staying in Touch...

Created and submitted by Hortense Gerardo

Do you have any upcoming events / programs that you want to highlight?

February 27, 2020: staged reading of FACE WORK made possible by a LAB grant from the Boston Foundation as part of the Asian American Playwright Collective (AAPC). https://aapcboston.wixsite.com/mysite/upcoming-events

March 20, 2020: full production of THE SAUNA PLAYS made possible by a grant from The Falmouth Cultural Council, a local agency which is supported by the Mass Cultural Council, a state agency. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/events/188999052501173/ https://www.salted.no/programme/2020/3/20/the-sauna-plays Tickets: https://www.universe.com/saunaplays200320

April 21, 22 & 24, 2020: full production of movement work, SMALL STEPS ON CLIMATE CHANGE as part of the Metropolitan Area Planning Council Artist Residency. https://www.mapc.org/staff-member/hortense-gerardo/

May 2, 2020: full production of THE MEDFIELD PROJECT as part of the Barr Foundation and the Metropolitan Area Planning Council Artist Residency. https://www.mapc.org/planning101/medfield-anthology-gives-audience-glimpse-of-past/

May 14, 15, 16 & 17, 2020: curation of THE MOVING MEMORY INCUBATOR: AN ACTION ART WORKSHOP at the Grange Hall Cultural Center https://www.grangehallcc.com/events/

How can people stay in touch?

www.hortensegerardo.com

Twitter: @hfgerardo

Filipinos In Boston: An Interview With Project Coordinator & Artist Anna Dugan

By Trish Fontanilla

I first met Anna Dugan last year at the Filipino Festival in Malden. She was selling some super cute stickers that I picked up, “You Had Me At Halo Halo” and “Kalamansi is My Main Squeeze,” to name two. She was at the beginning stages of launching her online store, so we held off for a little bit, but now that she’s rockin’ and rollin’, we figured it was time to highlight her!

Hope you enjoy our profile of Anna, and if you or someone you know wants to be highlighted on our blog or social media this year, you can fill out our nomination form.

Happy reading!

Where are you from?

Anna: I was born in Methuen, MA. My mom and her family are from Balayan, Batangas originally. A lot of family members have since moved closer to the Metro Manila area. And when I visit the Philippines, I usually stay with my Tita in Quezon City.

Where do you work and what do you do?

Anna: I work full time in Salem, MA as a project coordinator for a travel company. That job pays the bills as I pursue my career as a mural artist and illustrator. I am working hard to create more Filipinx representation around the East Coast and beyond.

What inspired you to pursue art?

Anna: I have always been a creative person. Ever since I can remember, I have loved everything art related. No matter what job I’ve worked in my adult life, I always found myself making time for the arts. Eventually, I realized that I needed to create things. It was part of me, and it was time to listen to myself and my desires to pursue it.

On Boston...

How long have you been in Boston?

Anna: I have lived in the area my whole life.

What are your favorite Boston spots:

Anna: Kaze Shabu Shabu in Chinatown is my absolute favorite restaurant to hit up in the city! Usually followed up with a fresh cream puff from Beard Papa. YUM.

On Filipino Food...

What's your all-time favorite Filipino dish?

Anna: Sinigang na baboy (sour and savory soup that has pork in a tamarind broth). It is the ultimate flavorful, comfort food. My mom also makes the best Filipino spaghetti.

What's your favorite Filipino recipe / dish to make?

Anna: I love making all kinds of soups - Sinigang, Nilaga (boiled meat and vegetable soup), and Tinola (Filipino chicken soup).

On Staying in Touch…

Do you have any upcoming events / programs that you want to highlight?

Anna: I am currently fundraising to send my painted balikbayan boxes to help aid people in the Philippines affected by the Taal Volcano eruption. People can donate to my GoFundMe to help pay for the contents of the boxes and the shipping costs OR they can donate physical goods. They can reach out to me on Instagram (@annadidathing) if they would like to drop off goods.

My family is originally from the Balayan area of Batangas. We are proud to be Batanguenos. And exemplifying the essence of kapwa, when our fellow man is in need we step up to help one another however we can. https://www.gofundme.com/f/north-shore-taal-volcano-relief

How can people stay in touch? (website / social / email if you want!)

Anna: Instagram: @annadidathing - Website: www.annadidathing.com

2020 Here We Come!

By Trish Fontanilla

Our top Instagram posts of 2019 // Created on the Top Nine app using our Instagram posts.

What. A. Year. Next week BOSFilipinos turns 2.5, and 2019 marked our 2nd full calendar year as an organization. Some of our milestones include…

60+ individual profiles about Filipinos / Filipino Americans across our blog and Instagram

6 general meetups around Boston (our next one is February 20th!), including our first ever community pot luck (thank you to everyone that contributed and special shout outs to Hyacinth Empinado and Katie Milliken)

2 community meetups: salsa dancing (thanks to community member Desiree Arevalo) and karaoke (thanks to our events contributor Mark Kcolrehs Cordova)

12 newsletters (one a month, and you can subscribe here)

14 videos filmed for #WordWednesday (thanks to multimedia content contributor Hyacinth Empinado)

20 blog posts (thanks to contributors Bianca Garcia, Reina Adriano, and Helena Berbano)

And we welcomed hundreds of new community members across our newsletter, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.

We are so incredibly excited about our 2020, and so thankful for all of our community supporters, whether you attended an event, contributed financially, or shared a tweet, we couldn’t have gotten through this year without you. We have a lot in store for next year, including more eatups, a podcast, and new community events. If there’s something you’d like to do with BOSFilipinos or if there are other ways for us to help, please let us know! You can comment below, email us at info@bosfilipinos.com, or DM us on Instagram or Facebook.

Manigong Bagong Taon (Happy New Year)! And I hope we have the opportunity to see you soon!